Enterprise Workflows Turn into a Cloud Asset

By 2026, “evaluating enterprise AI automation platforms: top 10 for 2026 security and scalability” has become a staple format for CIO briefings. That framing quietly reveals the real shift: workflows themselves are being pulled out of teams and embedded into centralized, AI-native control planes that sit in the cloud. What used to live as a mix of tribal knowledge, brittle scripts, and undocumented handoffs is turning into a managed, programmable asset governed by a handful of platforms.

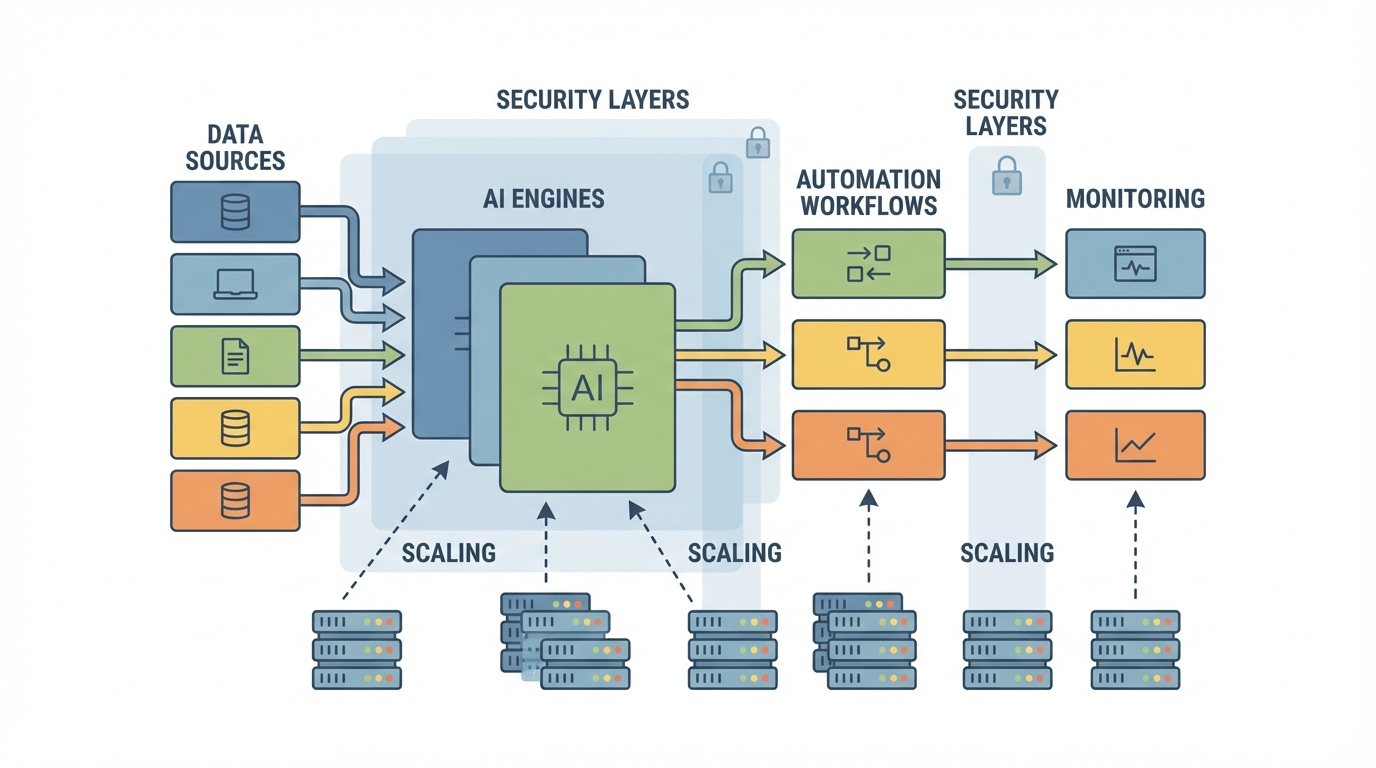

This category spans cloud-native agent frameworks from hyperscalers, specialist automation suites, and model-agnostic orchestration layers. The details differ, but the structural move is the same. Business logic migrates into a centralized automation layer; security and governance harden around that layer; and scale becomes a matter of provisioning compute and connectors rather than hiring and training people.

Security and scalability, on the surface, are evaluation criteria. Beneath that, they are the justification for turning human-shaped work into platform-shaped infrastructure. Once an organization accepts that the safest and most scalable way to operate is to codify workflows into an AI automation stack, leverage starts to concentrate around whoever owns that stack.

What It Does

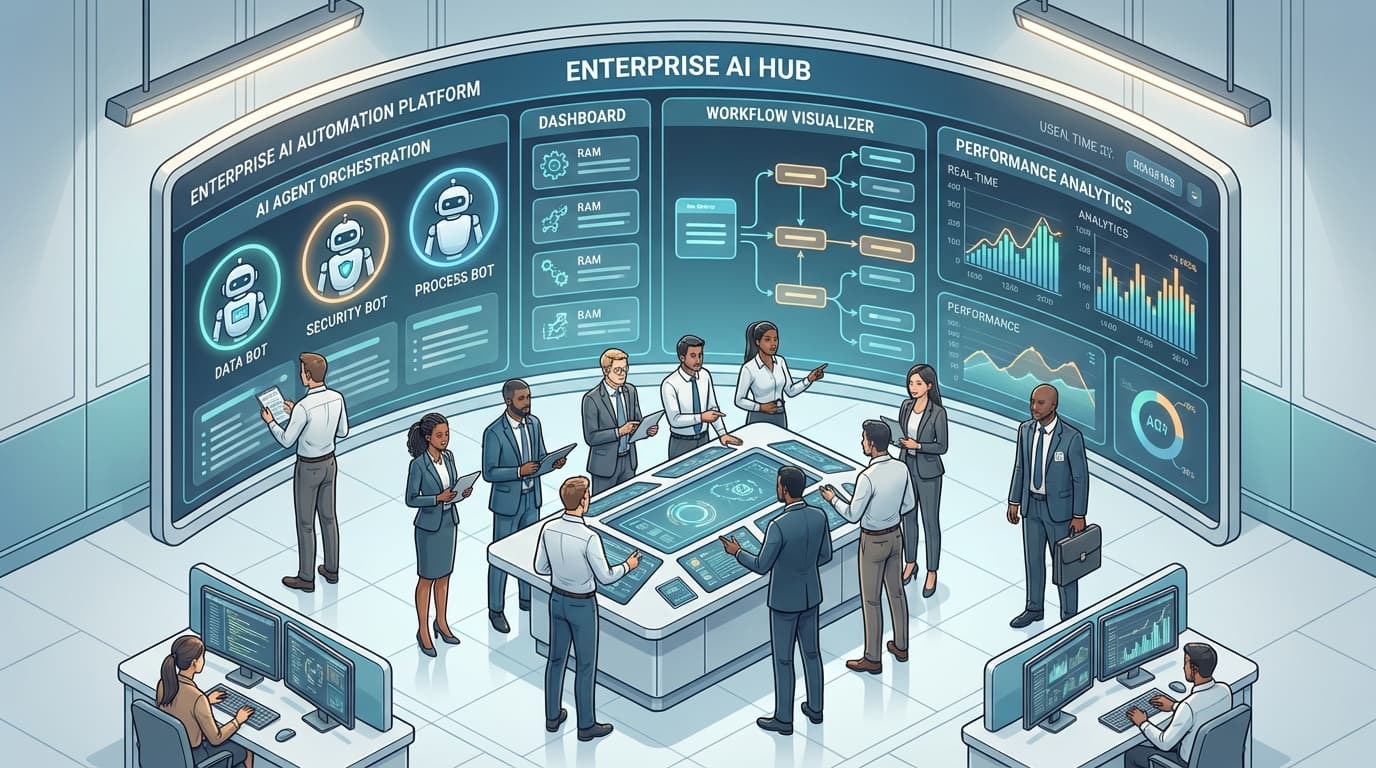

Enterprise AI automation platforms combine three historically separate domains: process automation, data access, and AI decision-making. They sit between employees, applications, and data stores, orchestrating how work moves and which agent or system executes each step.

At a concrete level, these platforms do the following:

- Connect to enterprise systems (CRM, ERP, HR, ticketing, custom databases) through managed connectors and APIs.

- Represent workflows as explicit graphs or state machines that determine how tasks progress, who or what is responsible, and which tools are invoked.

- Embed AI models and multi-agent systems that interpret unstructured input, make decisions, and call tools autonomously within policy constraints.

- Provide a control plane for identity, access, and policy: role-based permissions, data loss prevention rules, audit logging, and compliance reporting.

- Expose monitoring and observability, so teams can inspect runs, debug failures, and measure throughput, latency, and error patterns.

Security and scalability serve as the hard edges around this functionality. Security is enforced via encryption, network isolation, fine-grained permissions, and alignment with regulatory frameworks. Scalability is achieved by abstracting away infrastructure: serverless execution for agents, autoscaling workers, and centralized orchestration so new automations reuse the same governance and monitoring layers.

In previous generations, automation meant scattered RPA bots, bespoke scripts, or single-application workflows. The current platforms consolidate this into a unified layer. They aim to become the place where an enterprise describes “how we work,” and then lets AI-driven agents and bots execute that description at machine speed and cloud scale, under a single security envelope.

What It Absorbs

The existence of a coherent “top 10” of AI automation platforms signals not just product maturity, but a quiet commoditization of several human capabilities. These tools do not simply automate tasks; they absorb the skills involved in designing, coordinating, and safeguarding those tasks.

Process literacy and coordination are the first to be pulled in. Historically, understanding how work really flowed across departments required embedded operations people, veteran individual contributors, and line managers who knew every exception path. Today, process mining, event logs, and AI-assisted workflow design allow platforms to infer those flows directly from system behavior. The “map” of the organization’s work shifts from people’s heads and informal documents into a formal, machine-readable model that lives in the automation layer.

Integration craftsmanship is another casualty. The ability to glue systems together with scripts, custom APIs, or niche middleware has been a durable technical niche. Automation platforms standardize this into connector libraries, low-code builders, and configuration-driven orchestration. The unique value of knowing how to move data from system A to system B erodes when a platform vendor exposes that as a checkbox or template. What remains scarce is not integration technique, but access to the platform itself and permission to modify the shared process graph.

Operational judgment also gets partially codified. Many day-to-day decisions in support, finance, HR, and IT-whether to escalate, which queue to route to, which data source to trust-have lived as soft norms enforced by experienced staff. Multi-agent workflows with retrieval-augmented generation and tool use can now internalize these patterns. Over time, exception handling, routing rules, and escalation thresholds become policy objects in the control plane, tunable by a small governance group instead of distributed across hundreds of workers.

Even security and compliance expertise is being absorbed, though more slowly. Platforms ship with opinionated defaults: preconfigured data loss prevention rules, standardized access control patterns, reference architectures for regulated industries. Junior security personnel no longer need to design controls from scratch; they select from vendor-provided blueprints. The subtle ability to reason about risk trade-offs in messy, hybrid environments is compressed into toggleable options and best-practice templates created upstream.

What emerges is a separation between describing intent (“when this kind of ticket comes in, resolve it if…”) and implementing it safely at scale. The latter-once a complex blend of institutional knowledge, engineering skill, and operational judgment—is being repackaged as a service. That repackaging both raises the floor (fewer catastrophic mistakes for newcomers) and narrows the ceiling (less room for idiosyncratic, team-level optimization outside the platform’s model).

Who Gains, Who Loses

Centralizing workflows as a cloud asset shifts leverage along several fault lines inside large organizations and across the tech ecosystem.

Platform owners and hyperscalers are the most obvious beneficiaries. Once an enterprise encodes hundreds of workflows, policies, and access patterns into a particular automation stack, switching becomes expensive not just technically but politically. The platform now contains the living map of “how the company runs.” For hyperscalers that bundle automation with compute, storage, and identity, every new automated process deepens lock-in and drives incremental consumption of their broader cloud services.

CIOs, CISOs, and central IT gain a consolidated lever. Instead of chasing scripts and bots across departments, they can enforce security, data residency, and audit requirements through a single control plane. This consolidation reduces organizational chaos but also re-centralizes power. Line-of-business teams that once had latitude to spin up their own tools or shadow IT find themselves negotiating access to platform-level capabilities and quotas.

Operations consultants and process specialists see a mixed outcome. The low-end work—documenting basic processes, building simple integrations—erodes as platforms make that work push-button. In its place, a higher-leverage role appears: designing cross-organizational automation strategies, curating which processes to codify, and shaping governance policies. Those who can speak both “platform” and “business” gain strategic influence; those who depended on repetitive implementation work lose ground.

Frontline and back-office workers tend to lose informal power first, formal roles later. Their practical knowledge of edge cases and exceptions is mined—via observation, interviews, or co-design—into the platform. Once captured as rules and workflows, that knowledge stops being a bargaining chip. Headcount reductions may lag, but the structural bargaining position weakens as the organization’s dependency shifts from individual expertise to the uptime and correctness of the automation layer.

Mid-level managers face a subtler erosion. Many managerial roles have been anchored in coordinating work, enforcing process, and arbitrating exceptions. When coordination is handled by orchestration engines and exceptions are escalated according to policy trees, the managerial function tilts toward performance oversight and exception-signoff within parameters baked into the platform. The leverage to shape “how we work” moves upward to platform administrators and governance committees.

On the losing side at the ecosystem level, single-purpose SaaS tools that primarily automate linear workflows become overlays within someone else’s control plane. If an AI automation stack can replicate a tool’s value as “just another flow,” that tool’s differentiation vanishes unless it offers deep domain logic or proprietary data. The long-term gravity favors platforms that can represent entire process landscapes, not isolated tasks.

Regulators and auditors experience a temporary gain in visibility, as centralized logs and standardized controls make oversight easier. Over time, however, as more organizations converge on a handful of automation stacks, systemic risk concentrates. A subtle bug or misconfiguration in a widely adopted control plane can propagate across industries, shifting the locus of risk from individual organizations to shared infrastructure providers.

The Trajectory

If these platforms continue to succeed on their own terms—stronger security postures, predictable scalability, attractive “top 10” rankings—the next phase is normalization. The assumption becomes that any digital-first enterprise will express its operating model in an automation control plane. Not doing so looks irresponsible, the way running production workloads outside managed cloud once began to look.

In that world, new projects start from the platform outward. A proposed product, service, or department is evaluated partly by how gracefully it can be expressed as workflows and agents under existing governance. “Designing the org chart” quietly merges with “designing the automation graph,” and the latter is maintained by a smaller, more technical group with elevated access.

Security thinking shifts upstream. Rather than auditing individual applications, organizations treat the automation layer as the primary enforcement boundary: policies about data handling, geographic residency, and model choice become code in the control plane. The choice of platform starts to look less like a tooling decision and more like the selection of a semi-permanent institutional substrate, akin to a legal jurisdiction or accounting standard.

As automation coverage deepens, pressure grows for inter-platform portability: standardized representations of workflows, policies, and audit trails. If that pressure is resisted, lock-in hardens and the leverage of incumbent platforms increases. If portability standards emerge, a new market of “workflow brokers” and meta-governance tools appears, arbitraging between automation providers on cost, risk, and regulatory fit while maintaining a consistent process semantics for the organization.

For workers and managers, the long-run trajectory is a separation between roles that are inside the automation design loop and those that are merely subject to it. The former group works directly on the control plane: defining policies, shaping process graphs, curating models and tools. The latter performs residual tasks that are uneconomical or politically sensitive to automate. As more of the organization’s “memory of how to work” migrates into platforms, the strategic contest is no longer over individual tasks, but over who gets to write, read, and revise the source code of the enterprise itself.